|

All images and text are copyright protected. Contact

|

In the predawn winter darkness I lie half-awake awaiting one of the pleasures of Istanbul. And then it comes: "Allah-u ekber, Allah-u ekber ..." The first line of the ezan comes from the muezzin (cantor) of the nearby Sultan Ahmet Camii (the Blue Mosque) in Sultanahmet. The muezzin from the neighbouring Firuz Aga Mosque picks up the call: "Eshedu enla ilahe illallah ..." In the distance, on the wind, the other mosques Suleymaniye Camii and Yeni Cami summon the faithful: "Eshedu enla Nu hammedun resulullah ... "Five times daily, the ritual call to prayer is sung from the minarets in all Muslim countries. Turkey is 99% Muslim but the government is secular. "We," the Turks are proud to say, "have the best of both worlds." It is Ramadan, or, as it is known in Istanbul, Ramazan. During the day many Istanbullus keep the fast and attend mosque. At night, they attend the discos, dance, smoke and drink beer. Despite the strained relationships between Turkey and neighbouring Greece, the Istanbullu Greeks and Turks get along well - the most popular song played everywhere in Istanbul is Margarites by the Greek singer Angela Dimitriou. The Kurdish carpet shop salesmen still want independence or full autonomy but, more importantly, want to continue selling carpets in Istanbul. They may have a valid point. In 1924, Attaturk, the father of the Republic of Turkiye (Turkey) reformed the language, laws and culture and also suppressed the Kurdish culture in an attempt to assimilate them into the Turkish way of life. "How long before you gain independence?" I ask Tahir, a young Kurd from Kayseri in Cappadocia. He winks, "Two weeks."

In the evenings, after breaking the fast, Istanbullus throng the bazaar in the Hippodrome to feast on sweetmeats like hurma tatlisi, osmanli macunu and lokum. Or perhaps drink tea and listen to melancholy folk music. The men don western sweaters and trousers, the women wear long dresses, a coat and often a scarf or veil called a yashmak. Later, during the three-day holiday at the end of Ramazan, the bazaar is unexpectedly empty. The Muslims are all celebrating at home or at the homes of families and friends. Istanbul straddles the Bosphorus. Western Istanbul lies in Europe, the eastern bit in Asia. It is of some significance to me. I am on my way to China and want to step from Europe to Asia on 1 January 2001 - a symbolic departure from the West to the East. In 1999 I journeyed among the Uyghurs (people of Turkic descent) throughout Xinjiang in north-west China. The Uyghurs were largely nomadic until two generations ago and their history is written in the sands of the Taklamakan Desert in the cities of Kashgar, Turpan and Urumuqi. In the eleventh century, the Selcuk Turks fled westward from the Mongols in central Asia and by the mid-fifteenth century, as the Ottomans, had conquered much of Eastern Europe. I looked for links between these two cousins but the language was of no help to me - Uyghur words that I had picked up were unrelated to modern Turkish. The Istanbullus did not know if Uyghurs ever came to Turkey and were largely unconcerned. Yet, the Uyghur culture could still be seen in the midst of modern Istanbul: the crowded maze of bazaars with clusters of shops specialising in leather, silk, gold, brass or spices; the elegant and formal manner of greetings; the ritual of chai (tea)...  The ferry over the Bosphorus to Uskudar in Asian Istanbul is pleasant. The Bosphorus Bridge, seen in the distance spanning Europe and Asia, is the fourth longest suspension bridge in the world. It shines like a gossamer spider's web, seemingly too slender to support the motor traffic.

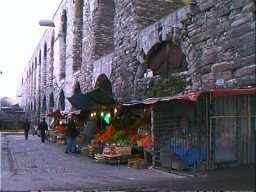

The ferry over the Bosphorus to Uskudar in Asian Istanbul is pleasant. The Bosphorus Bridge, seen in the distance spanning Europe and Asia, is the fourth longest suspension bridge in the world. It shines like a gossamer spider's web, seemingly too slender to support the motor traffic. My childhood impression of Istanbul as a crowded medieval city, dark and dangerous with intrigue, could possibly be true of the Old City but is dispelled by the Turks in Uskudar. They chat politely and offer me cups of sweet Turkish tea without expecting payment. Unlike in the Old City, there are no carpet salesmen, no tourist junk shops and, lo, very few tourists. Istanbul is a mix of historic monuments and modern buildings. Mosques, palaces and bath-houses are maintained in near original condition. Shops and homes have been renovated for convenience and new offices like banks and Attaturk Airport are quite modern. In Beyoglu, the tiny subway runs for about 700 meters up the hill and the quaint early 20th century tram takes me one kilometer to Taksim, the business centre of Istanbul. The Metro, built more for durability than looks, is free during Seker Bayrami the three-day holiday at the end of Ramazan. I ride the rails to the western end and hop off at various points to walk. Just off the main road, the side streets quickly become neighbourhoods of children kicking a football, men sitting in the weak sun enjoying a chat and women walking quickly home carrying armloads of groceries. In Zeytinburnu I chat briefly with an old man outside a mosque. He had kept the fast and hopes to do hajj in Mecca before he dies. In Seyitniz I hand out sweets to the children, the tradition during Seker Bayrami. In a tiny café on a tiny side street I stop to eat. The elderly cook and his wife ply me with mounds of bread and point to the broken, empty, metal cage high up on the wall from where their television was stolen the previous night. At Topkapi, along the city walls, a group of children trail noisily after me wanting to be photographed. "You want a woman?" they cry laughingly. I buy persimmons for 400,000 Turkish lira and chicken doner (sandwich) for 1 million Turkish lira. At Fatih Mosque I buy a tesbih (Muslim rosary). Two boys in the forecourt explain that the thirty-three beads are to keep track of reciting eleven times each: "Allah ekber", "Bismillehirrehmenirrehim" and "Elhamdurillah". Inside, a Professor of Islamic Studies translates for me a notice on the walls: "He who fasts for 6 extra days following Ramazan will be blessed by Allah as if he had fasted for a whole year." He himself will fast for the six extra days. "It is good for the soul," he says. Sultanahmet is packed with history. Topkapi Palace, with its famous Harem, was home to three centuries of Sultans who slaughtered each other for the Sultanate. Besides treasures like emerald studded daggers and crowns, it also houses a footprint in stone and a strand of hair from the Prophet Muhammed and the hand of John the Baptist.

The Blue Mosque was built 400 years ago to surpass the beauty of Aya Sofya. After Rome fell, Constantinople became the centre of the Eastern Roman Empire. The church Sancta Sophia (as Aya Sofya was known then) was the centre of Christendom until the Muslim Ottoman armies overran the city in 1453 and converted the church into a mosque. And across the road from it is the ruined marble milestone, The Milion, which marked the centre of the Byzantium Empire. The Obelisk of Theodosius was brought from Egypt to Constantinople in 390 AD and The Basilica Cistern is an underground water tank that sort of looks like a church under water. There are a few remaining cobblestone twisty lanes lined with bright cafes and carpet shops. The Turks dress accordingly in post WW2 coats; some trendy young ones struggle to create a splash but Istanbullus generally look entrenched in the late Fifties with their morose demeanor and drab, practical clothes.  At the beautiful Yeni Mosque I sit eating a pear in the forecourt. A kindly middle aged man quietly interrupts to ask if I am Japanese. He is a retired vet whose aged mother had recently passed on and he immediately had problems from his in-laws

demanding a share of the estate. "Very shocking it was too. My formerly gentle sister-in-law suddenly turned vicious and said some nasty things to me about my mother. I lost control and hit her. I don't regret it now. Anyhow, I've paid them off and hope never to see them again. Nowadays I spend my time reading and taking quiet walks."

At the beautiful Yeni Mosque I sit eating a pear in the forecourt. A kindly middle aged man quietly interrupts to ask if I am Japanese. He is a retired vet whose aged mother had recently passed on and he immediately had problems from his in-laws

demanding a share of the estate. "Very shocking it was too. My formerly gentle sister-in-law suddenly turned vicious and said some nasty things to me about my mother. I lost control and hit her. I don't regret it now. Anyhow, I've paid them off and hope never to see them again. Nowadays I spend my time reading and taking quiet walks."At the busy labyrinthine Covered Bazaar I buy a painting of Egyptian gods on papyrus. "It's from Egypt," says the salesman. "Genuine papyrus. Look!" He crumples the painting and smoothens it out again, none the worse for the demonstration. I haggle for 20 minutes for several blue glass evil eye protectors (nazar boncogu) to protect me from evil salesmen but they were never very effective. I try a variety of foods: chicken doner, semit (a tough doughnut), ayram (a sour yoghurt) with fruit, lamb kebaps on skewers and plain bread and cheese with a bottle of mineral water. I attempt several sweets like Turkish delight and sweet rice pudding but they are almost always far too sweet. On most evenings I venture down the hill to Eminonu to have a typical Turkish dinner at a tiny two-table café where the diners quickly come and go. There is delicious thick lentil soup, aubergine stew, an excellent bread and tea. For dessert there is usually Turkish coffee. I skip the Turkish raki, an anise flavoured brandy which the Turks, and only Turks, are addicted to. At the Turkish Baths (hamam), Martin (a poet-philosopher Quebecois) and I are given pestemals (wrap cloths) for the bath and shown to the caldarium (hot room) to lie on the central marble slab heated from underneath by steam. After half an hour I am grateful for a sluice of cold water and then back for another half hour of steaming. A shampoo, scrub and a massage makes me forget that winter waits outside. After the bath we lie wrapped in towels in our cubicle for an hour sipping tea and discuss poetry and life in an evening of civilised pleasures. Upon my arrival in Istanbul the first of many carpet salesmen pounced. "I know the way. Allow me to show you to your hotel," he offered. He showed me instead to his carpet shop where he offered me a cup of red tea and unrolled several types of kilims and carpets explaining each in great detail. After my third yawn he reluctantly allowed that he'd made a mistake and that my hotel was actually in another street. He kindly let me go and, at his door, pointed out my street to me.

Every day in Istanbul I am accosted by at least four or five carpet salesmen inviting me to have a look. Cetin is one such. He strikes up a conversation with me as I sit reading in the Hippodrome. He was living in Germany but is now helping in his sister's restaurant and is also selling carpets. Only for the winter. He really wants to be an actor and is taking a modelling course as a first step. His favourite actors? Robert de Niro, Bruce Willis, Mel Gibson. Favourite film? Braveheart. We talk about film and acting for over three hours until we are weary. "I have spent all afternoon chatting without taking back one customer," he says. "Would you mind coming back to the showroom to keep my boss happy?" "I wouldn't be interested, but I might have dinner at your restaurant if the prices are reasonable." The food is quite good and the bill is higher than my usual. Cetin looks embarrassed. The following day he explains. "You know, my job is to encourage customers, anyhow I can, to eat at that restaurant and to buy carpets and kilims even if they don't want. I must do that if I am to get commission. I need to make commission to survive." "I knew that," I say. "I didn't mind. The food was good." "When I first spoke with you, you were just a customer. But then we talked about film and I learned many things. I have never talked about film in that way before. So when I took you to the restaurant, I felt very bad. I didn't want you to pay. But, I, too, could not afford to pay for it." "It's okay. I enjoyed the meal." "I don't like this job lying to people. In Antalya where I was born, we are not like that. I don't like Istanbul but I cannot make a lot of money in Antalya." I wonder suspiciously if this is another scam but hasten to reassure him, "Don't worry about it. It's okay." New Year's Eve catches me without plans for midnight. Preferring my own entertainment, I turn down the party with the tired belly dancer. I have dinner at the usual little café and afterward buy a bottle of Turkish white wine, a stick of bread, half a kilo of cheese and black olives. Late in the night I sit and eat in my window gazing out at the heavy buttresses and pencil slim minarets of the beautiful spotlit Aya Sofya while the old year goes out. At farewells, the Turks say, "Gule gule." Go smiling. Raceandhistory.com | Howcomyoucom.com | Trinicenter.com | TriniView.com Another 100% non-profit Website serving poorly represented communities. Copyright & Disclaimer. - - Privacy Policy --Designed & maintained by S.E.L.F. © 2002 TriniView.com |