All images and text are copyright protected.

For license to reproduce contact

|

All images and text are copyright protected.

|

|

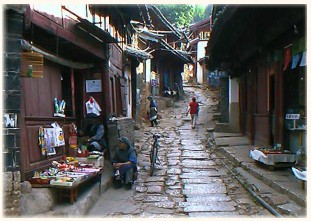

4 hours north of Dali and 500 m higher lies Lijiang at the foot of the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain. Here, at 2400 m above sea level, I find it difficult to breathe and develop an aversion to the many coal fires which I imagine to be sucking up my share of precious oxygen. Lijiang, and especially Lijiang Old Town, is the home of the Naxi (also written Nakhi and Nahi) minority. The Old Town is crammed with traditional Naxi homes, markets and shops in a jumble of cobblestone alleys and a maze of canals. Most cars, trucks and motorbikes are banned from the Old Town, keeping it pollution-free and adding to the charm of a town caught in a time warp.  In the market square Mr Yang, who describes himself as a "foolish old boy of 80 years", sits writing poetry. "Many centuries ago during the Warring Period the Naxi were Tibetan nomads in Gansu province," he says in very good English which he learned from the Austro-American botanist Joseph Rock in the 1930's. "They fled the war and went to Xinjiang, then to Tibet and finally came down to Yunnan.

They first lived in Baisha and then moved to Lijiang where they split into three groups. The ones who remained here were called Naxi, the ones who moved to Dali were called the Bai and the ones who moved to Lugu Lake were called the

Mosuo." Even today the three groups share similar customs though the Mosuo have remained the most faithful to the traditional ways.

In the market square Mr Yang, who describes himself as a "foolish old boy of 80 years", sits writing poetry. "Many centuries ago during the Warring Period the Naxi were Tibetan nomads in Gansu province," he says in very good English which he learned from the Austro-American botanist Joseph Rock in the 1930's. "They fled the war and went to Xinjiang, then to Tibet and finally came down to Yunnan.

They first lived in Baisha and then moved to Lijiang where they split into three groups. The ones who remained here were called Naxi, the ones who moved to Dali were called the Bai and the ones who moved to Lugu Lake were called the

Mosuo." Even today the three groups share similar customs though the Mosuo have remained the most faithful to the traditional ways.The Naxis (especially the Mosuo) are the last matriarchal society in the world and practitioners of the only pictograph language still in use today which they claim can be read by anyone without being taught. Their culture, religion and shamans, all called Dongba, have existed, like their music, for over one thousand years. Originally a blend of animistic and ancestor worship, their Dongba religion has now incorporated Lamaism, Islam and Taoism. "Before the earthquakes in 1996 and 1997 not many people knew of Lijiang," says Kitty, a Naxi guide. "There were very few tourists and the Old Town was not as bright as it is now." The earthquakes were a major turning point in the fortunes of Lijiang putting the town in the media worldwide and getting listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. 'Discovered' by the trendy westerner tourists, the town has been quickly westernised with cafes, guesthouses, boutiques and souvenir stalls catering to the American dollar. "I arrived in the night," says Marianne, "and thought I was in a tourist site. All that strip lighting outlining the rooftops along the main street reminded me of Disneyland." The Naxis are concerned about the number of Han Chinese who come in from outside provinces to rent and turn their homes into cafes and guesthouses. The Naxis enjoy the income but they fear that the town is losing its Naxi atmosphere and spirit since the landlord Naxis move to the New Town to live in modern brick and concrete Han style apartments. Why don't they keep their own properties and open their own cafes and guest houses? Some do but the vast majority of Naxis are too honest to compete against the Han Chinese.  Outside of the town centre the back alleys have remained the same for 800 years. I spend most evenings rambling along the winding lanes that lead me in circles over bridges and past canals bordered with weeping willows which remind me of a miniature Amsterdam. "The Naxi architecture has changed," says Kitty. "Long ago the Naxi houses looked like log cabins but about three hundred years ago they began copying the Bai houses in Dali. The shell of the house is made of stone blocks or mud bricks and the inside walls and beams are of wood which are flexible enough to cope with the earthquakes. In the recent earthquakes many of the Han buildings fell down but the Naxi homes were safe."

Outside of the town centre the back alleys have remained the same for 800 years. I spend most evenings rambling along the winding lanes that lead me in circles over bridges and past canals bordered with weeping willows which remind me of a miniature Amsterdam. "The Naxi architecture has changed," says Kitty. "Long ago the Naxi houses looked like log cabins but about three hundred years ago they began copying the Bai houses in Dali. The shell of the house is made of stone blocks or mud bricks and the inside walls and beams are of wood which are flexible enough to cope with the earthquakes. In the recent earthquakes many of the Han buildings fell down but the Naxi homes were safe."The new buildings remain true to the traditional methods of building and within one year of being built the new houses already look quite old. "The winters here are mild," says Mama Fu, a smiling motherly restaurant owner. "It snows every sixteen years and most winters are just like autumn." "When did it last snow?" "Fifteen years ago." One morning toward the end of winter it snows for half an hour. The children run out and dance in the snow. They, like me, have never seen snow close up though the top of the neighboring Jade Dragon Snow Mountain is covered permanently in snow.

"Have you ever been up Jade Dragon Snow Mountain?" I ask. Mama Fu looks at me in mock horror. "You must not ask Naxi people this question," she says. "Long ago, if young Naxi couples were refused permission to marry they would go to Love Suicide Hill on Jade Dragon Snow Mountain." These days people can safely ascend and return in a modern chairlift. I take a room in a typical Naxi home on a hill overlooking the Old Town. There is a central courtyard bounded on three sides by the living quarters and kitchen. Here live three generations of family: the grandparents, the son and his wife and their daughter. The grandmother speaks Naxi dialect and very little Mandarin, wears traditional Naxi clothes and rules the household. The son dresses in Han Chinese style, speaks both Naxi dialect and Mandarin, works in the evenings and potters about in his garden in the courtyard. The grand-daughter understands Naxi dialect but speaks only Mandarin, a trend that shows the slow decay of tradition. The young generation also sticks mainly to Han Chinese clothes; the Naxi girls avoid the unattractive blue and white apron of the older women and adopt a colourful red, yellow and blue costume for tourism purposes. Some traditions though are still very much alive. In a tradition that goes back further than living memory, at dawn every morning in summer, the Naxi men gather at the Big Stone Bridge with their hawks to compare and share advice. And every Saturday evening a bonfire is lit in the market place around which the Naxi grannies along with a few Mosuo, Bai and tourists dance in circles in a social evening called gou huo wan hui. The music is bouncy and danceable. The grannies have a stately step, the younger ones prance boisterously, the tourists trip uncertainly. The circles, like life, grow bigger, break apart, form new ones, come together. After two or three hours the decaying fires and the deepening night brings everything to an end.  Chong Ren is a Bai young man who now works and lives in Lijiang. "The Bai have a wedding tradition. After the ceremony, the bride and groom go to their new home and race for the pillow. Whoever wins the race is the boss of the home. When you marry will you also do this?" I ask.

Chong Ren is a Bai young man who now works and lives in Lijiang. "The Bai have a wedding tradition. After the ceremony, the bride and groom go to their new home and race for the pillow. Whoever wins the race is the boss of the home. When you marry will you also do this?" I ask.He smiles in amusement. "I am not racing for the pillow. When I marry I will be the boss." "In a Naxi home the wife is always the boss. If you marry a Naxi girl, who will be the boss?" He looks puzzled. "I cannot marry a Naxi. I am a Bai, I must marry a Bai." "If you wanted to write to your mother how would you do it?" "There is no written Bai language. I could write in Chinese but my mother cannot read Chinese." "What then would you do?" "I would telephone to her." The Year of the Rabbit comes to a close. The markets throng with shoppers buying red clothes (red being the color of happiness), live chickens, fish and pig's head, incense and Hell money to burn for the ancestors, duilian or couplets written on red paper to paste on doorways, balloons, windmills, fireworks and firecrackers for the children and shui xian or narcissus flowers for the home. In the New Town, Naxi grannies turn to glance at the brand new 30 meter computerized advertising screen then continue on their way home. The Naxis practise in secret for the festivities to open the Year of the Dragon with music, song and dance. In the market place small performances are given on a newly erected stage and in the stadium, for the television cameras, large groups of brightly costumed Naxi, Bai, Mosuo, Yi and Tibetan dancers form lines, circles and arabesques in a colorful spectacle like a living mandala. I met Mr Yang again sitting in the marketplace. He presented me with a fan on which he had written in Dongba, Chinese and English: "I have been to the Dayan town of Lijiang County. To my nice friend with an enjoyable offering." "Thank you," I say. "It is wonderful. What can I give you in return?" "It is a gift," he replies. "You can say, 'Thank you'. It is enough." "Jjyu byye seh," I say in his dialect. Thank you. The Sichuan-Tibet Highway: The Northern Route | North-west China : The Silk Road | China : The Centre of the World Journey to Shangri La: Yunnan | Journey to Shangri La: Dali | Journey to Shangri La: Lijiang Journey to Shangri La: Zhongdian & Deqin | The Year of the Dragon |